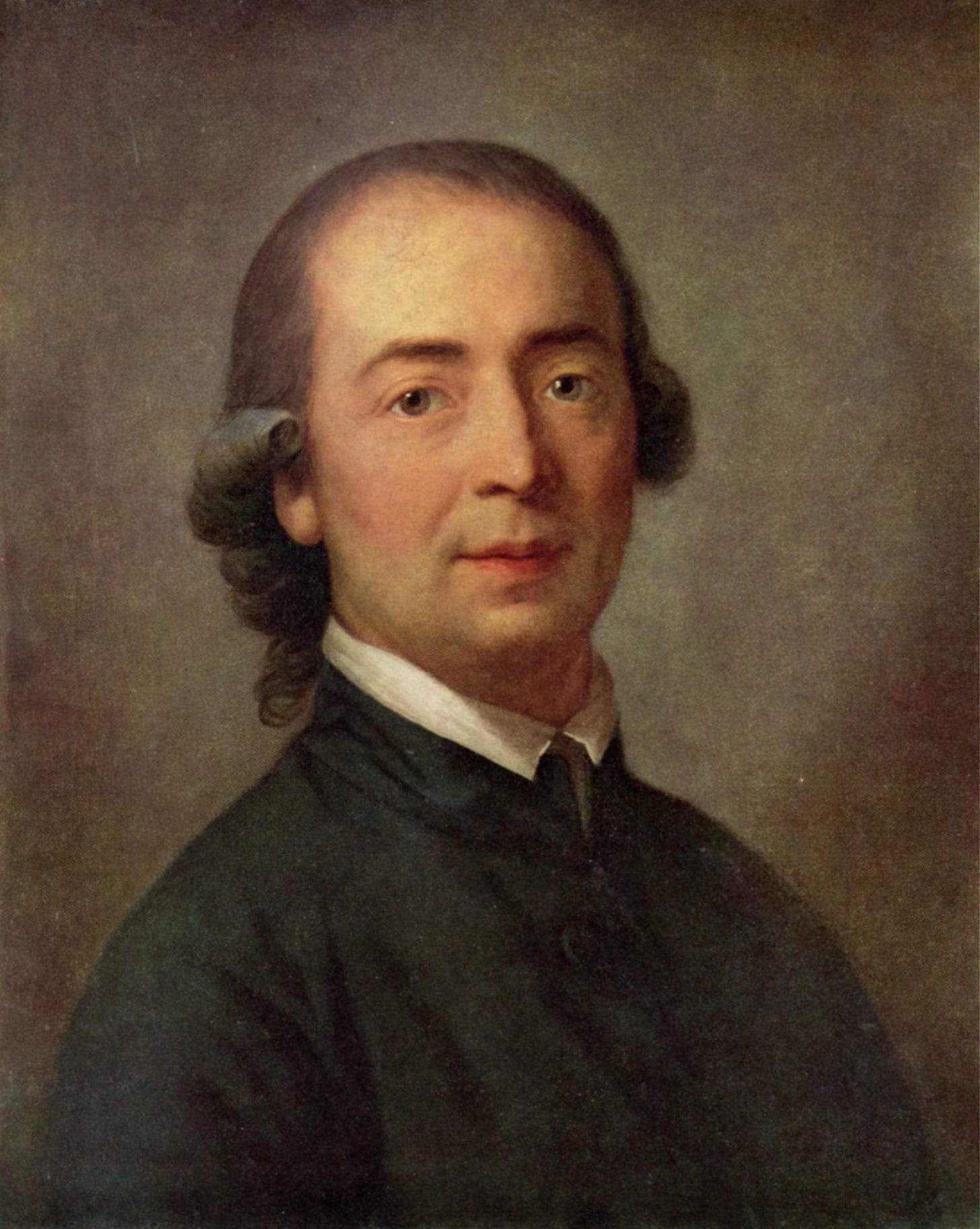

Where I discuss “Treatise on the Origin of Language” by J.G. Herder

While at times belaboured, this was a hugely stimulating read.

I came at this essay from two directions. First, that this was one of the thinkers who had a profound influence on Isaiah Berlin’s thought, and Berlin was - and is - one of the thinkers who has shaped my view of the world. Second, that Herder laid the groundwork for anthropology, a field of study I think deserves to be appreciated far more than it is.

In other words, I came with high expectations. While I was eventually fulfilled, the journey was far from straightforward. To understand why, we have to understand the argument that Herder sets out to make.

Herder is attempting to disprove the idea that language is of divine origin.

Now that would strike us moderns as somewhat silly (of course it isn’t divine) and hardly worth arguing, but it is the route Herder takes to make his argument that offers insights.

The first topic tackled is a study of the properties of the senses.

Hearing, to Herder, is a special sense. To understand why, we can contrast it with vision. Vision is overwhelming - it floods us with information.

Consider, Herder says without a trace of tongue in cheek, the sight of a sheep impinging on your eyes. To conclude that it’s a trivial bit of information would be a mistake. There’s so much detail in that ordinary picture: the variation in tones and highlights and shadows amidst the colour; as well as the textures, and the movement, and infinitely diminishing detail into the horizon. Every pixel of that picture in front of you is packed with too much information to process. The conclusion that it’s a simple picture of a sheep cannot happen just with visual sense perception, but has to be mediated by an act of reasoning and abstraction.

Hearing isn’t that way. With hearing, there’s direction - of sound waves and in time - and for that reason, and others, it is more simply graspable as an experience. The sound of a sheep’s bleat is really what leads us to the first act of abstraction - may bleating things be called sheep - that would eventually make visual perception trivial.

Hearing, unlike vision, is warm, to Herder. Unlike vision, we can make sounds back. Insofar as our vocal organs permit it, we can imitate the sound of a bleating sheep. It’s a two-way sense.

Herder draws a comparison with the sense of touch and smell too, concluding that hearing is more suitable to language for similar, but diametrically opposite, reasons to vision.

Here, you could raise the objection that many of these things are subject to empirical study. Many in my philosophy study group certainly did. I think Herder is too slippery to be easily boxed into “sense thinking”. To Herder, going too far into isolating the senses would be a mistake.

“We are a single thinking sensorium commune, only touched from various sides. There lies the explanation.”

When the senses are separated, they become more like mechanical sensing instruments. By way of our conceptual sleight of hand, we’ve made them amenable to easy laboratory study. This, to Herder, would miss the crux of the argument. Hearing is isolated only to show why language has sound. But ultimately, what language is doing is making characteristic marks on the experience of a human soul.

What Herder calls the “soul” sounds a lot to me like what we might call the first person subjective experience of consciousness, the qualia if you will. (On a side note, I’m now wondering if the dismissal of all pre-enlightenment “soul” talk has actually thrown the baby out with the bathwater.) This emerges from an awareness of the fusion of sensorial input, but in no simple, reductive way.

I may have seen that sheep many times before, but this time is different. I see that sheep while sitting in a comfortable lounge chair amid a field of petunias. I am in quite a nostalgic mood, vaguely thinking of a time when factory smoke didn’t choke the air. The combination of sensory input and mood make a particular unit of mental experience.

I am so struck by the feeling of that experience that I decide to make a characteristic mark on it. I might choose to call the mark “sheepful”.

Herder spends much time dismantling the arguments for the divine origin of language. What law forces people to use these arbitrary sounds and immensely complex grammatical rules called language, ask the believers.

He charges them with a lack of imagination. I am reminded, unavoidably perhaps, of creationists who appeal to absurdity when they ask “how many years would it take for a fish to turn into a Booker prize winning author?”

Time, time, and more time, Herder would thunder. The scale of time over which the complexity of language we see around us arose lies beyond easy imagining. But Herder tries. By asking us to imagine ourselves as the first humans in the world, he seeks to build in us a conviction that yes, those miniscule acts of making characteristic marks and language and reason and sound, operating over thousands of generations, could create something so complex and apparently designed like language.

But Herder rejects the design of language too. The Arabs have a thousand words for “sword”. What creator would call that well-designed? It would make sense if instead a thousand different tribes named sword-like things differently, and then all the tribes merged, but all the words stayed.

To those who make a subtler argument, that the thousand words for “sword” had slightly different meanings once, but have lost the nuances with time, Herder asks - why is the divine creator so inefficient as to make a thousand words for gradations that are only going to be lost?

Again, it is far more sensible to suppose that as the drawing of characteristic marks on units of experience, many similar things may have had differences once. Then both outcomes could be similarly conceivable - that the fine gradations were significant once, but no longer, but also that equivalent things were named differently by different people.

Until this point, all of Herder’s work only goes as far as to show that language could have emerged. Herder is also determined to show that language had to have emerged.

We are reminded how weak human beings really are. We don’t have fierce claws or overwhelming strength. We are poor predators and easy prey going by the ordinary rules of nature. What we do have is the ability to “clearly and distinctly” organise the world around and within. To Herder, this inevitably leads to language, as language is how we make characteristic marks, that are then built into abstractions and concepts and stories and formulae using reason, and we need all this to survive.

When this is combined with the human need for sociality, the puzzle completes. As deep as the desire for food or drink is the desire to communicate and listen to other humans. Parents instruct children in not just the circle of ideas they themselves learnt, but also the characteristic marks they’ve made in their own lives. This is the gift of the whole of the experience of their lives, handed down as the ultimate act of love. Children learn these, to a degree, but always modifying, rejecting, imbibing in tune with their own units of experience.

And so it is that language must have been so.

The moments of drudgery apart, which I chalk down to poor formatting (in the text I read), and perhaps translation issues, I was - firstly - entertained. I do appreciate the intellectual pleasure of attempting to explain a thing from first principles. (Imagine you are the first human in the whole world.)

Part of my feeling comes from Herder’s unexpected passion. He is contemptuous of the cold philosopher, who, sitting in his comfortable armchair, wonders how so marvellous a thing as language could have been created by us limited humans. The argument I’ve described already, but what strikes me is that Herder’s words evoke what he says.

I’ve seen Herder positioned as an anti-enlightenment thinker. I’m not sure I read that from this text. He makes no attempt to topple Reason from her exalted pedestal. To Herder, the spark of reason is what makes us human, and which has a better claim to the spark of divinity. Where he departs from the leading lights of the Enlightenment is that he finds it perfectly reasonable that language marches in lockstep with reason to build us the glorious abstractions that make up human knowledge.

To Herder, it is silly to exalt reason only while treating language as an uninteresting epiphenomenon. Without the characteristic marks of language, the spark of reason has nothing to work on and does nothing. This is no trivial academic dispute, because Herder’s conviction led him inevitably to a rejection of Eurocentrism, just as the standard enlightenment position led to Eurocentrism.

Given how there are many different ways of making characteristic marks on the infinity of experience, and different ways of expressing, bequeathing, and communicating them, it is reasonable to Herder that there could be other, equally valid set of answers to the human conditions than European ones. He draws examples from world cultures to make his point. Each time he shows how Siam is different, or Ceylon, or the Eastern languages, each time he does so without seeing inferiority in those languages, he lays the first building blocks for anthropology and pluralism. He carves out room for multiple peaks in the summit of the human condition.

Condamine merely says that it is so unpronounceable and distinctively organized that where they pronounce three or four syllables we would have to write seven or eight, and yet we would still not have written them completely. Does that mean that it Is longwinded, eight-syllabled? And “difficult, most cumbersome” – For whom is it so except for foreigners? And they are supposed to make improvements in it for foreigners? To improve it for an arriving Frenchman who hardly ever learns any language except his own without mutilating it, and hence to Frenchify it, But is it the case that the Orenocks have not yet formed anything in their language, indeed not yet formed for themselves any language, just because they do not choose to exchange the genius which is so peculiarly theirs for a foreigner who comes sailing along?

I shouldn’t go too far. While Herder is radical in his respect for the “savages”, he is still a man of his time. I’m fairly sure he does see progress in language, and that French is more evolved than the “Eastern” tongues. However, he is more sympathetic to the difference being more of a change, than mere progress.

Ultimately, the strongest impression Herder leaves me with is an appreciation for the vitality of language. Language is no fixed snapshot, it never has been, and it never will be. It is constantly being shaped anew by each speaker and each listener, and through the vast dance of expression we’re all a part of, we’re inextricably linked.

Each individual is a human being; consequently, he continues to think for the whole chain of his life. Each individual is a son or daughter, was educated [gebildet] through instruction; consequently, he always inherited a share of the thought-treasures of his ancestors early on, and will pass them down in his own way to others. Hence in a certain way there is “no thought, no invention, no perfection which does not reach further, almost ad infinitum.” Just as I can perform no action, think no thought, that does not have a natural effect on the whole immeasurable sphere of my existence, likewise neither I nor any creature of my kind [Gattung] can do so without also having an effect with each [action or thought] for the whole kind and for the continuing totality of the whole kind. Each [action or thought] always produces a large or small wave: each changes the condition of the individual soul, and hence the totality of these conditions; always has an effect on others, changes something in these as well – the first thought in the first human soul is connected with the last thought in the last human soul.